A version of this post previously appeared on .

Technology and data have transformed the way we live, work and play. So far, the outcomes have been mixed. While we are undoubtedly more connected and better informed, weãre simultaneously more anxious about the pace of change and our personal privacy. And rightly so. Last yearãs showed us just how easily our personal data can be amassed, extracted and exploited for political gain. Looked at another way, though, technology and data have the potential, if harnessed for good, to alleviate some of the worldãs most pressing global challenges - including climate change, global pandemics and human trafficking.

Data on its own is not the answer. Never in human history have we had access to so much data. The challenge is that most of it sits in silos, leaving us with an incomplete picture of complex social issues. Take human trafficking as an example. Around 172 countries form part of the chain of exploitation, while more than 40 million people are enslaved per year. Itãs a daunting picture. The only way to drill down into whatãs really going on, and to develop intervention strategies, is for data to be shared.

Letãs see what happens when two quite simple principles ã harnessing data for good and data-sharing ã are put into action to tackle human trafficking.

Human trafficking is a $150 billion global business hiding in plain sight. Very few of us are aware of the statistics, to say nothing of the fact that itãs likely happening right in our own backyards. And until recently, it was next to impossible to track and assess the entire trafficking supply chain ã from the financing to the brokers to the victims and the buyers. Data-sharing has upended all of this.

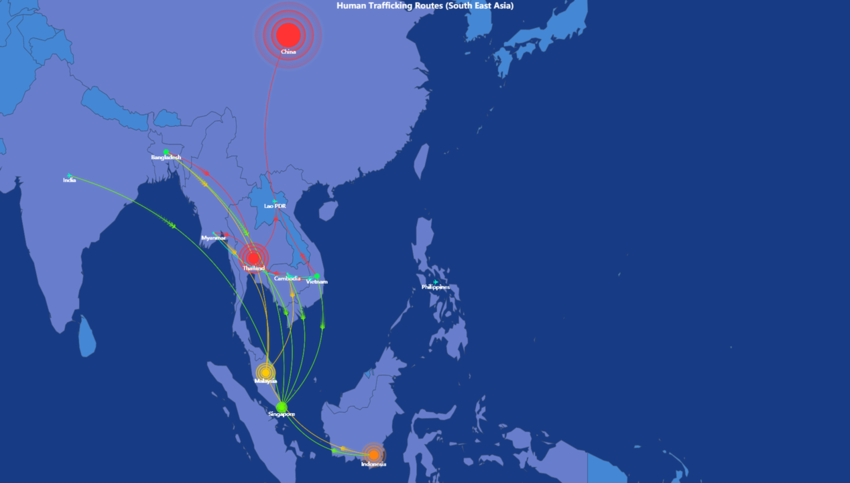

For the past 13 years, , a non-profit, has used the power of people and technology to combat human trafficking. It recently asked the ¥¨âøòÆóç Predictive Intelligence Centre, a team of data and behavioral scientists focused on leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI) for marketing and communications, to come on board. Weãve built the organization a human-trafficking prevention model that relies on data-sharing between numerous sources, particularly non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and financial institutions, alongside crowdsourced and open-sourced data. IBMãs data hub and visualization platform consolidates the intelligence and produces insights about illicit trafficking operations such as market supply and demand, trafficking routes and financial flows.

Itãs impossible to overstate the pivotal role NGOs play in the trafficking prevention supply chain. Theyãre the only source with enough detail about specific cases to be able to establish specifics like the price a person is sold for, and where and through whom recruitment is conducted. From this, we can decipher which technology platforms are being used for victim recruitment, which ports victims are transferred through, and even which airlines they are transported on. Armed with this data, machine-learning techniques are applied to aggregate case data. We gather intel from different NGOs, open-source news articles, court cases and crowd-sourced data through Stop the Traffikãs , a phone application allowing anyone to submit suspicious activity anonymously and securely.

In aggregate, the data allows us to identify trafficking hotspots and patterns, which are then shared with stakeholders that have been flagged as having links to trafficking-related activities. For example, if our findings identify a particular airline route with a high rate of child trafficking victims, the airline can respond along that specific route right away, and immediate measures can be taken to engage law enforcement before the victim reaches the designated destination.

Likewise, banks can be alerted when suspicious activity is flagged up by the data. On their own, financial institutions struggle to identify and disrupt trafficking-related transactions because their data models cannot distinguish money-laundering transactions from trafficking ones. Fortunately, together with data sharing, this all becomes possible. Financial data can be combined with existing NGO and open-source data to identify specific signs of trafficking and the risk level of particular transactions and accounts. With these results, banks can now validate and improve their machine-learning models and educate staff to better identify trafficking-related transactions. They can also train front line staff to identify trafficking brokers, which can ultimately freeze financial flows of all the intermediaries involved in the trafficking supply chain.

There are undoubtedly malign forces at play in the world of Big Data. All too often our personal data is being manipulated for financial or political gain. Itãs no wonder we feel threatened, vulnerable and powerless when it comes to our own data. But what about those who are powerless to begin with? Shockingly, for every 10,000 people in the world, nearly 54 of those individuals are victims of modern slavery, with a quarter being children. Not only do the victims have no rights, but theyãre walking among us and living in our communities, and yet weãre largely unaware. Indeed, the trafficking industry has thrived in part because there is no central intelligence hub. This is precisely why we need to harness data for good ã because through data sharing, we can work to eradicate one of the most longstanding, evil and unjust social issues of our time.

Bob Grove is chief operating officer, ¥¨âøòÆóç in APAC.

Anjuli Bedi is associate director, Analytics and Psychometrics, ¥¨âøòÆóç Predictive Intelligence Centre.