In the 2021 ╝½└ų╩ėŲĄ Trust Barometer, the UK finds itself in its lowest ever position in a league table of trust, just one place off the bottom with only Russia below it. How did the birthplace of parliamentary democracy, the ŌĆ£mother of parliaments,ŌĆØ and a respected voice of sense on the world stage find itself in such an unaccustomed place? After all, the Trust Barometer is a global ranking of trust in the very institutions for which the rest of the world has often admired the UK. What exactly precipitated this fall from grace?

To live in the UK today is certainly to experience a very different atmosphere from the one that existed only two decades ago, before the financial crisis, before the post-Cold War euphoria became a hangover of uncertainty.

A toxicity has overtaken the tone of the UKŌĆÖs internal conversation. Politicians of every party, including the Prime Minister, have taken to attacking the BBC, which other countries regard as a beacon of impartiality, for its bias. Other parts of the UK media openly attack the judiciary in a nation where the separation of powers has been a given for four centuries. And everyone, from MPs to schoolchildren, has taken to attacking each other on social media.

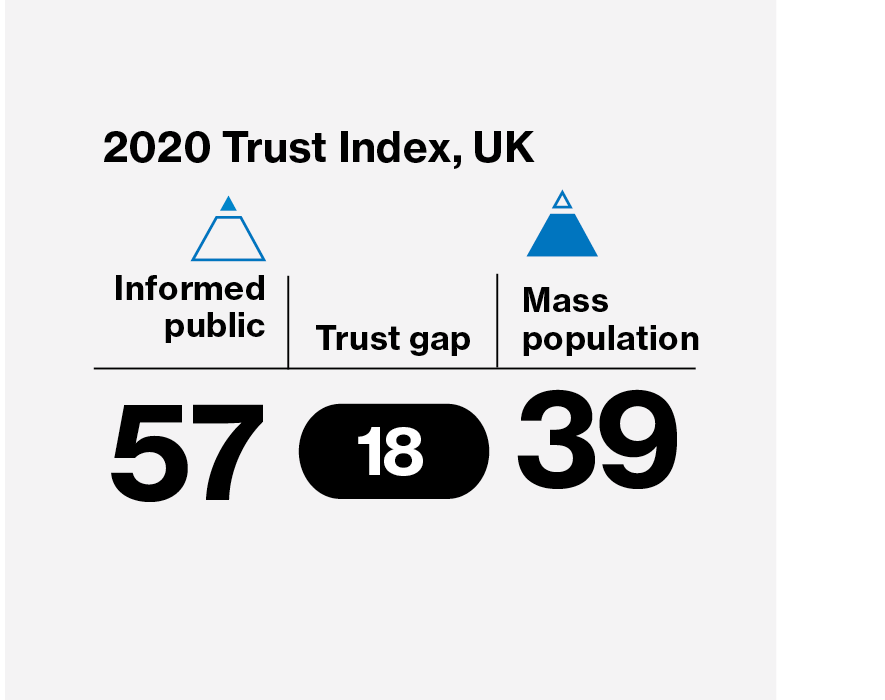

Little wonder then that the general population in Britain now distrusts its institutions with a trust score of only 42 percent. ╝½└ų╩ėŲĄ has also found a gaping trust gap between attitudes of the wealthier, more educated and more well-informed in society versus the rest (an 18-point gap). Even so, that informed public group has some fundamental worries of its own. Almost 70 percent of them agree with the sentiment that ŌĆ£democracy is losing its effectiveness as a form of government.ŌĆØ That is a stunning 14 15.5 percentage points higher than the average for the other members of the G7 group of advanced economies. Among the general population, itŌĆÖs 60 percent.

Think about that for a moment: the cradle of parliamentary government, the defender of free speech, bastion of the rule of law, appears to be losing faith in the idea of democracy itself. Not only that, but BritainŌĆÖs attitude to capitalism is changing. The country that gave the world its first financial capital ŌĆō the City of London ŌĆō is falling out of love with business-as-usual too. In the UK today, 63 percent of the informed public and 53 percent of the general population agree that ŌĆ£capitalism as it exists today does more harm than good in the world.ŌĆØ

Profound questions are being raised about globalization and unrestrained technological change, about how they fuel inequality and unfairness. Automation and downward economic mobility are stoking fears around job security. All of which is driving distrust in the UK, and to a far greater extent than the global average, the British people see their institutions as unethical.

You might well say, and you would be largely right, that other countries have gone through all the pressures and exhibited all the symptoms described above. There are two special factors, though; first, the UK is lower in trust and higher in disdain for institutions than almost all its peer group of nations; second, that peer group, and the rest of the world, just doesnŌĆÖt expect Brits to be like this ŌĆō such expressions of angst contradict the caricature of reserve and resolve.

Examining our 2020 findings, the explanation for these changes do in fact offer lessons for other nations.

Because it would be a mistake to think that Brexit alone was to blame for this collective loss of trust in our institutions, or indeed that somehow the UK is an outlier. Brexit is the easy answer, but it is not as simple as that.

While Brexit did prove to be the spark that lit the gunpowder, the conditions were set by years of institutional failures - the financial crash; the MPs expenses scandal; phone hacking and the advent of fake news on social platforms; and the Oxfam scandal in Haiti ŌĆō that had already rocked trust in business, government, media and NGOs.

British institutions failed to recognise what happened and how to respond to it. They were too slow. Too bureaucratic. Not agile enough. Then, the failure to deliver Brexit ŌĆō which had been an argument narrowly won by a British desire to ŌĆ£Take Back ControlŌĆØ ŌĆō demonstrated how little control voters actually had. This disillusionment in turn injected that poisonous tone into our political discourse and consequently damaged trust in business and the media too among the informed public.

Banks after all have largely continued to behave like banks, politicians like politicians and journalists like journalists. There may have been reforms from within, but they are not easily visible from without. No wonder that when politicians dithered and then delayed over delivery, the voters put their foot down.

In the early hours of December 13, 2019, as the general election results came in, we found out the response to three years of drift: Millions of people who no longer trusted our institutions lent their votes instead to a man with not inconsiderable issues of his own aroundŌĆ” trust.

Boris Johnson won with a simple message: ŌĆ£Get Brexit Done.ŌĆØ But voters were also voting to reject the bitter stalemate that had settled on the UK. They backed ŌĆ£doing stuffŌĆØ over more argument.

The Brexit debate leads to the natural conclusion that BritainŌĆÖs problems are the exception. But looking at the Trust Barometer and frankly the issues that many European countries face, all that has changed is that Britain is, unusually, the pacesetter. France is after all beset by yellow-jacketed weekly protests over pension reforms. Spain is divided over Catalan independence. Italy is unified only by constant political upheaval. Germany seeing the far right come from nowhere and trust in its gold-plated country brand collapsing. All four countries have institutional trust levels among the general population that are under 50 percent.

The challenge then for our institutions, whether in Britain, or most developed countries, is how to respond to the change that citizens from all walks of life are calling for. Undoubtedly, the way in which business and government co-operate will determine how they are judged. The results of special trust study we performed among the UK population shows that their reputations are inextricably linked in the minds of two-thirds of the British public, and three quarters want them to collaborate to solve social issues.

Our political and corporate leaders are on notice: incrementalism is no longer enough. Instead people are looking for big, bold change to deliver a discernible improvement in their lives. Quite possibly, given the erosion of trust in democracy and capitalism, it may also mean reform in order to make the system work better for those our institutions have left behind. Ultimately, it will require the reimagining of our institutions and systems. It is the scale of that change ŌĆō economic, political, and societal ŌĆō and the shape of that reform, that will ultimately determine whether we can repair trust in our core institutions.

Ed Williams is President and CEO of ╝½└ų╩ėŲĄ's EMEA region.